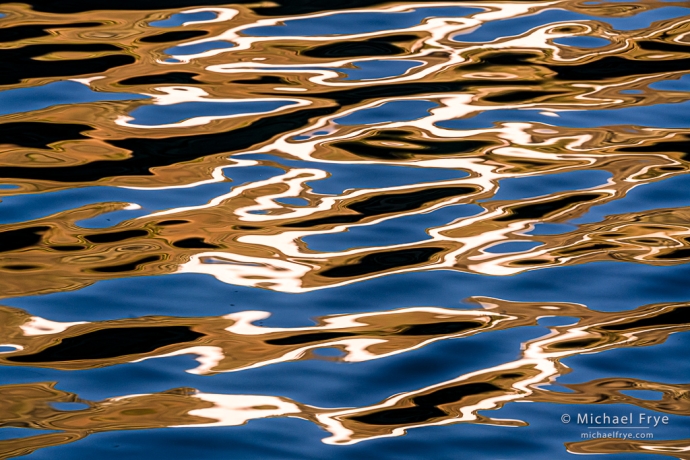

Ripples and reflections in an alpine lake, Inyo NF, California. 227mm, 1/125 sec. at f/22, ISO 1250.

During our Range of Light workshop in July we found some striking reflections in a mountain lake. These weren’t mirror reflections, because a nearby cascade was pouring into the lake, rippling the surface of the water. But that’s actually what made the reflections so interesting. The ripples created squiggly lines and shapes in the water, as the surface reflected blue sky and late-day, golden light shining on rocks and snowbanks across the lake.

It was a great situation for making abstract images, so I encouraged our participants to zoom in with a long lens to try to capture the patterns. While I often like using slow shutter speeds for water images, capturing these ripples required fast shutter speeds to freeze the water’s motion and preserve the intricate patterns. And the patterns would be more prominent if everything was in focus, which required stopping down the aperture to get as much depth of field as possible.

I ended up using 1/125 sec. at f/22 most of the time. And with those settings, in the relatively low light at the time, I needed to push up the ISO to 1250, or even higher. But I knew I could crank up the noise reduction later in software to remove any noise that might appear, without sacrificing sharpness, because there weren’t any solid objects in the frame that needed to be super crisp.

Since the ripples were moving so rapidly, the only way to catch the best moments, when the patterns were most interesting, was to fire off a lot of frames, then pick out the best ones later. I captured at least 200 frames, and picked out just two here: the one above, and the first one below. (The last image below is another water abstract made in the Grand Canyon last year.)

I’ve always enjoyed viewing and making abstract photographs. Maybe that comes from my art background, and the influence of abstract expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock.

But even if you don’t love abstracts as much as I do, I think there’s value in learning to see abstractly. That means thinking about design more than subject. It means paying attention to the lines and shapes of the scene in front of you, and figuring out how to arrange those lines and shapes into a coherent, compelling design. Whether your subject is big or small, near or far, a strong design will strengthen any composition. The first photograph in my last post, for example, is a big, sweeping landscape scene. But does the image have a design? You bet. Would it work as well if it didn’t have that design? I don’t think so.

And one of the best ways to learn to see abstractly, to learn to create designs within your viewfinder, is to look for opportunities to make abstract compositions, where the “subject” of the photo is lines, shapes, or patterns. The more you look for these things, the more you’ll train your eye to find them, and the more you’ll notice the structure and design of every scene and subject.

— Michael Frye

Related Posts: Clearing Tropical Storm; Desert Designs; Abstract Vision

Michael Frye is a professional photographer specializing in landscapes and nature. He is the author or principal photographer of The Photographer’s Guide to Yosemite, Yosemite Meditations, Yosemite Meditations for Women, Yosemite Meditations for Adventurers, and Digital Landscape Photography: In the Footsteps of Ansel Adams and the Great Masters. He has also written three eBooks: Light & Land: Landscapes in the Digital Darkroom, Exposure for Outdoor Photography, and Landscapes in Lightroom: The Essential Step-by-Step Guide. Michael has written numerous magazine articles on the art and technique of photography, and his images have been published in over thirty countries around the world. Michael has lived either in or near Yosemite National Park since 1983, currently residing just outside the park in Mariposa, California.

I appreciate the detail you provide in these narratives. Very useful information and provides lots of fun things to try in the field.

Thanks Chuck! Glad you like the posts.